A Brief History of Printing

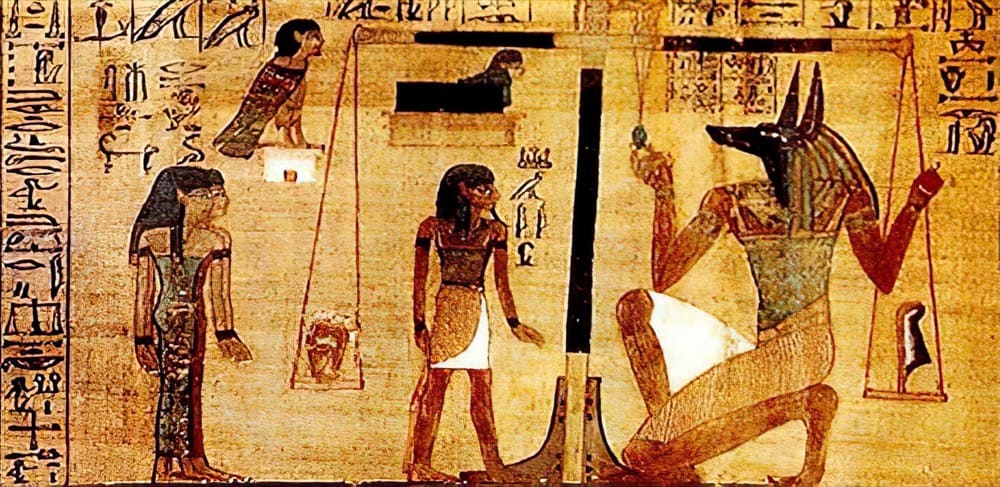

Egyptian Papyrus: 4000 BC

Papyrus is the ancient Egyptians invention for writing paper, and it was the most important writing material in the ancient world. The word “paper” is derived from “papyrus” - an ancient Egyptian term that originally meant “that which belongs to the house” i.e. the bureaucracy of ancient Egypt.

Papyrus is a common marsh plant having a triangular reed that used to grow along the banks of the river Nile. The paper was made from the pith of a papyrus. Each stem was stripped of it is rind and cut into short pieces which were then cut lengthwise into narrow strips. The papyrus pith was kept soaked in water until the fibers become flexible and translucent.

Two layers of papyrus strips arranged at right angles were put on a hard flat object and beaten or pressed to desorb the water until they fused together. The resulting sheets were left to dry in the direct sun for several days, then they were polished and glued together to form scrolls.

Babylonian Signet Stones: 2300 BC

The application of signet stones is possibly the earliest known form of printing. They were used in ancient times in Babylonia and elsewhere, apparently both as substitutes for signatures and as religious symbols.

The devices consisted of seals and stamps for making impressions in clay, or of stones with designs cut or scratched on the surface. The stone, often set in a ring, was dabbed with pigment or mud and pressed against a smooth, resilient surface in order to make an impression.

Confucian Engravings: 2nd - 8th Century AD

The emperor of China commands, in AD 175, that the six main classics of Confucianism be carved in stone. Confucian scholars are eager to own these important texts. Now, instead of having them expensively written out, they can make their own copies.

Simply by laying sheets of paper on the engraved slabs and rubbing all over with charcoal or graphite, they can take away a text in white letters on a black ground – a technique more familiar in recent centuries in the form of brass-rubbing.

It is a natural next step to carve the letters in a raised form (and in mirror writing) and then to apply ink to the surface of the letters. When this ink is transferred to paper, the letters appear in black (or in a colour) against the white of the paper – much more pleasant to the eye than white on black.

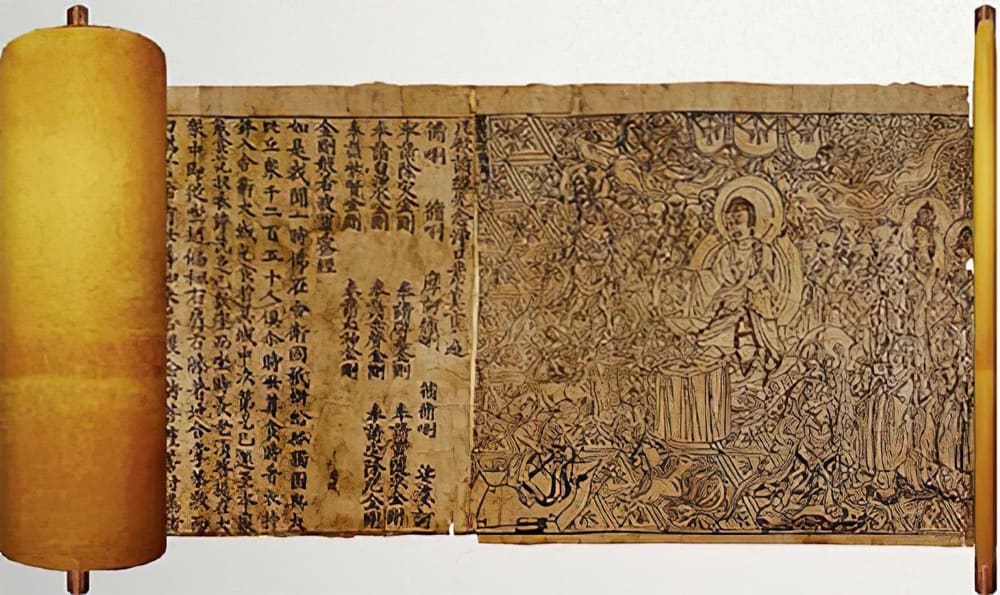

Buddhist Woodcuts: 868 AD

The Diamond Sutra is the world’s earliest-known printed book, dating back to the end of the T’ang dynasty in 868 AD. Discovered in a cave at Dunhuang in 1899, it is a precisely dated document which brings the circumstances of its creation vividly to life.

It is a scroll, 16 feet long and a foot high, formed of sheets of paper glued together at their edges. The first sheet in the scroll has an added distinction. It is the world’s first printed illustration, depicting an enthroned Buddha surrounded by holy attendants.

The pages are printed from pieces of wood in which the white areas on the page have been carefully cut away, until the remaining parts of the flat surface represent (in reverse) the shapes to be printed. The flat surface is covered with ink, a page is placed on it and rubbed to transfer the ink.

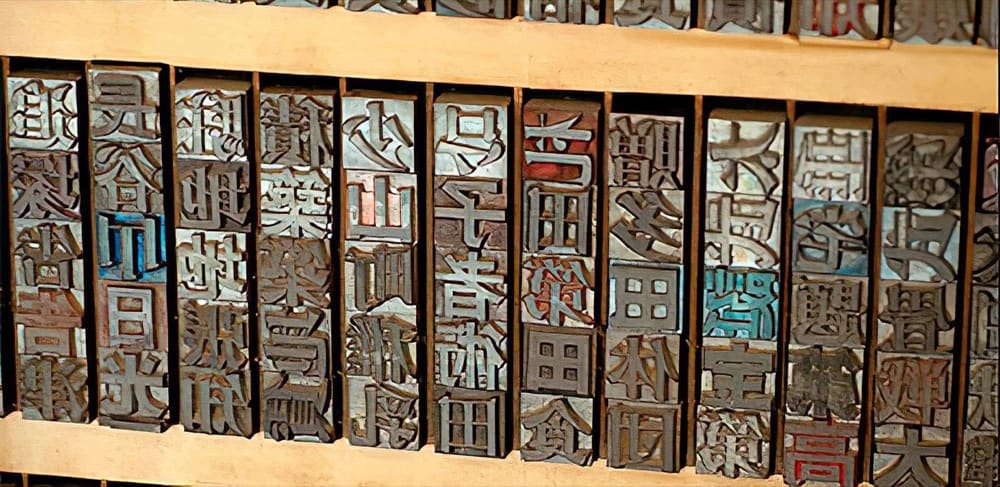

Movable Type: 11th Century

Movable type is a system of separate ready-made characters or letters which can be arranged in the correct order for a particular text and then reused. The concept is experimented with in China as early as the 11th century.

However, two considerations make the experiment unpractical. One is that the Chinese script has so many characters that whole process becomes too complex. The other is that the Chinese printers cast their characters in clay and then fire them as pottery, a substance too fragile for the purpose.

This method becomes more widely used when introduced to western civilization around 1400 AD, when printing luminary, Johannes Gutenberg, employed the use of metal rather than clay. Since the western alphabet is phonetic and not symbolic, this system also proved to be much more practical.

Intaglio Printing: 1300-1500 AD

The origins of intaglio printing (also called gravure) were with the creative artists of the Italian Renaissance in the 1300s. Fine engravings and etchings were cut by hand into soft copper.

The Italian word intaglio (in-tal-yo) means engraved or cut in. As a printing method, intaglio refers to an image carrier that consists of lines or dots recessed below the surface, reproducing an original design by pressing paper into the recesses.

Gutenberg and Western Printing: 1439 - 1457 AD

Johannes Gutenberg was an innovator of his time. He revolutionized the mechanics of the printing press, allowing it to apply a rapid but steady downward pressure. A former goldsmith, Gutenberg also pioneered the manufacture of movable type in metal pieces.

His first publication is a full-length Bible in Latin (the Vulgate). No date appears in this book, which was printed simultaneously on six presses during the mid-1450s. In 1457, his first dated book is even more impressive. Known as the Mainz psalter, it achieves outstanding colour printing in its two-colour initial letters.

These first two publications from Germany’s presses are of an extraordinary standard, caused no doubt by the commercial need to compete with manuscripts. The new technology, so brilliantly launched, spreads rapidly.

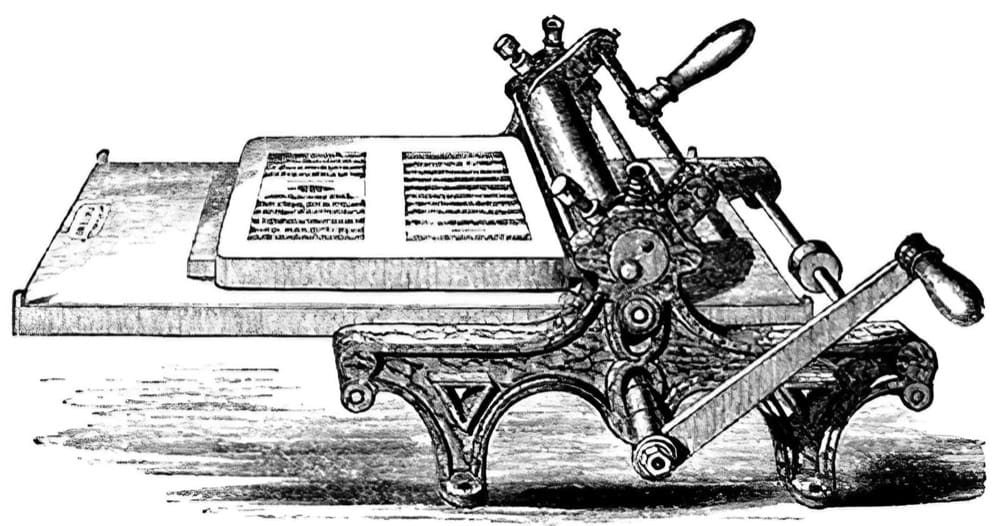

Screw Press Enhanced: 1600 AD

The screw press was improved for the first time since Gutenberg’s day with the introduction of springs to aid the platen to lift rapidly. It was then able to print a maximum of 250 impressions an hour.

Newspapers began to appear. They developed from newsletters and printed pamphlets. The relationship between advertising and newspapers enabled both to flourish from the early 17th century. The printed medium changed advertising from announcements to persuasion.

Mezzotint: 17th - 18th century

The first printing process to achieve a fully tonal effect is pioneered in the late 1650s by prince Rupert of the Rhine. It is immediately given a name reflecting its ability to print halftones – Mezzo Tinto (Italian for ‘half tinted’). A good mezzotint has the quality of a black-and-white photograph.

Hard work is involved in creating a mezzotint. A copper plate is roughened all over by striking it with a curved metal blade with sharp teeth. The resulting rough metal surface holds the printer’s ink in all its recesses, and if inked all over will print a velvety black tone.

This blackness can be modified in any part of the print, through every tone of grey to pure white, by rubbing the plate’s pitted surface to differing degrees of smoothness (any area rubbed completely smooth will hold no ink and thus will print as a white patch).

With this technology the printers of the 17th and 18th centuries can reproduce every subtle shade of tone in an oil painting. For the first time entirely convincing portraits are reproduced in fairly large numbers – at a cost which remains high, but which is much less than the previous custom of having oil copies made.

Aquatint: 1768-1830

In about 1768 a French artist, Jean Baptiste Le Prince, discovers a way of achieving tone on a copper plate without the hard labour involved in mezzotint.

His technique is to sprinkle on a fine dust of powdered resin, fuse the grains to the metal by heat and then submit the plate to the acid of the etching bath. The acid eats away at the exposed metal surface around and between the grains, resulting when printed in a fine mesh of black ink around white spaces.

Le Prince’s invention of aquatint gives printmakers for the first time the option of using areas of tone in an etching, to give an effect much like that of a wash drawing.

The first great artist to appreciate the full potential of aquatint is Goya. He uses it in the eighty prints of the Caprichos, published in 1799, and then again with the eighty-two plates of The Disasters of War. Goya is also the first great artist to make effective use of the next discovery in printing, that of lithography.

Lithography: 1799 -1837

Lithography was invented by Alois Senefelder in Bohemia in 1796. In the early days of lithography, a smooth piece of limestone was used (hence the name “lithography”—”lithos” (λιθος) is the ancient Greek word for stone).

After the oil-based image was put on the surface, acid burned the image onto the surface; gum arabic, a water soluble solution, was then applied, sticking only to the non-oily surface and sealing it. During printing, water adhered to the gum surfaces and avoided the oily parts, while the ink did the opposite.

Senefelder had experimented in the early 1800s with multicolor lithography; in his 1819 book, he predicted that the process would eventually be perfected and used to reproduce paintings.

Multi-color printing was introduced through a new process developed by Godefroy Engelmann (France) in 1837 known as Chromolithography. A separate stone was used for each colour, and a print went through the press separately for each stone.

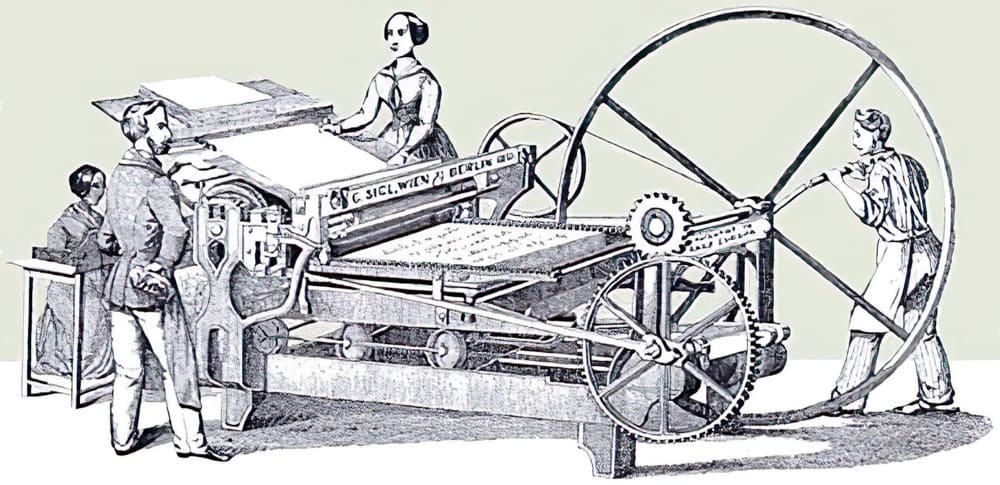

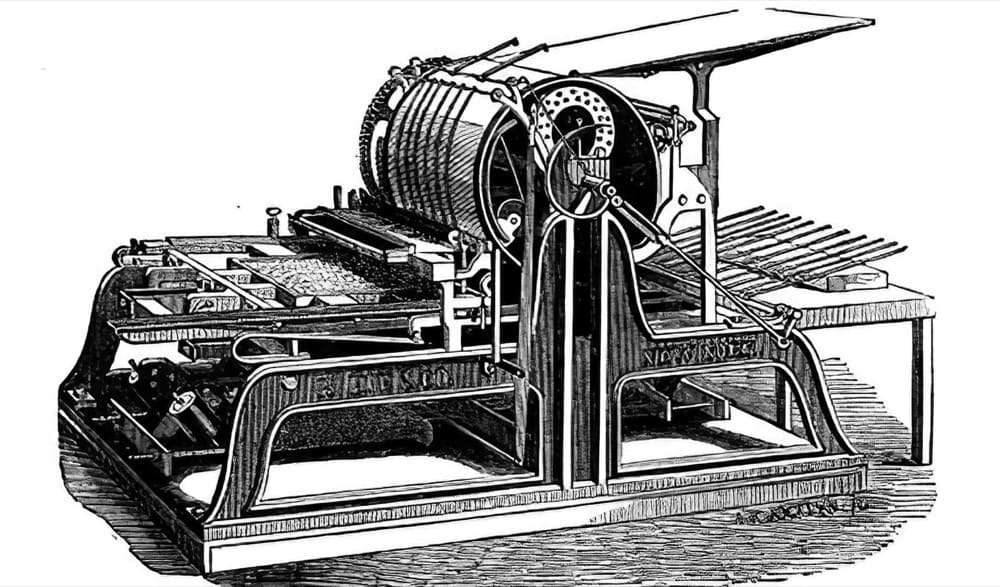

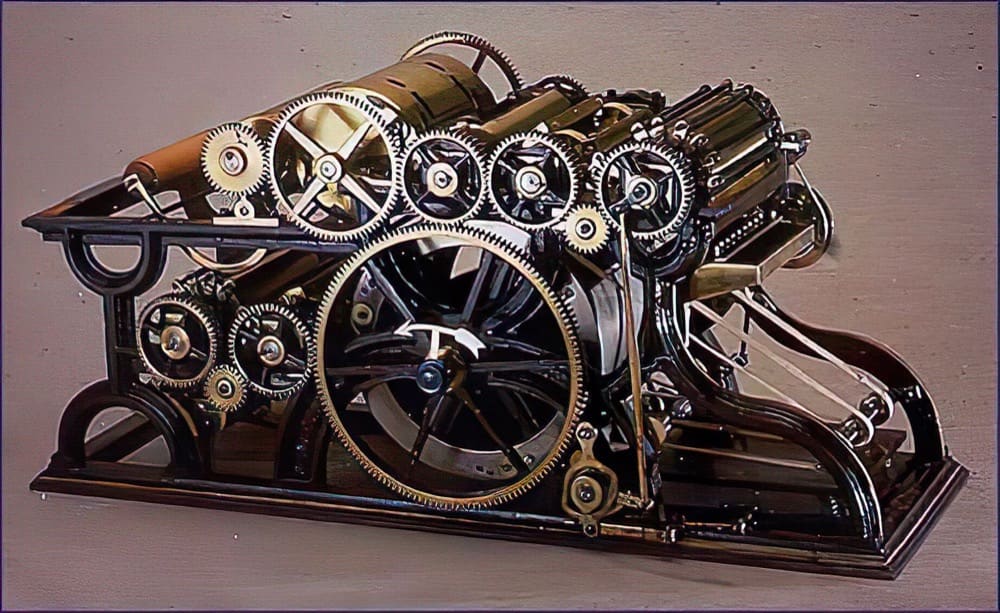

Mechanized Printing: 1812 - 1832

In 1812, Friedrik Koenig invented the steam-driven printing process and dramatically sped up printing. The Koenig Press could print 400 sheets per hour.

In 1824, Daniel Treadwell of Boston expanded on this concept. By adding gears and power to a wooden-framed platen press, the bed-and-platen press was four times faster than a handpress. This type of press was used throughout the nineteenth century and produced high-quality prints.

Richard Hoe, an American press maker made improvements to Koenig’s design, and in 1832 produced the Single Small Cylinder Press. In a cylinder press, a piece of paper is pressed between a flat surface and a cylinder in which a curved plate is attached. The cylinder then rolls over the substrate and produces an impression.

The cylinder presses were much faster than platen and hand presses and could print between 1,000 and 4,000 impressions per hour.

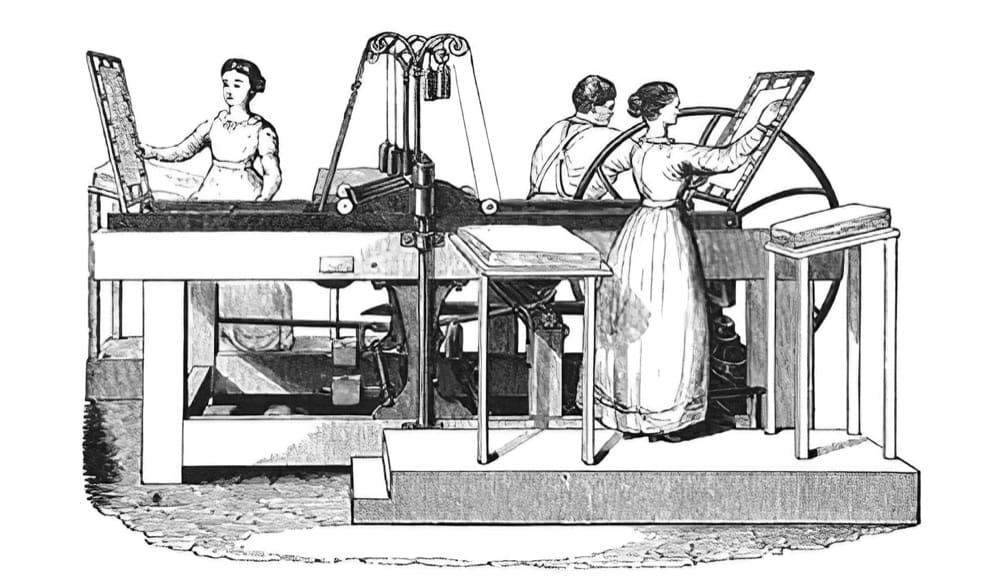

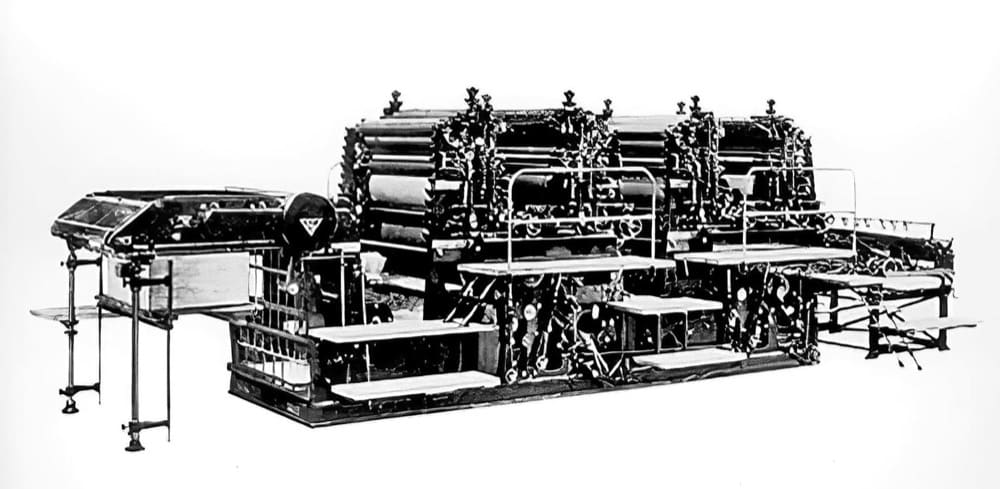

Rotary Press Invented: 1843

In 1844, Richard Hoe invented the rotary press. A rotary press prints on paper when it passes between two cylinders; one cylinder supports the paper, and the other cylinder contains the print plates or mounted type. The first rotary press could print up to 8,000 copies per hour. Larger rotary presses, containing multiple machines, made printing large newspaper runs possible.

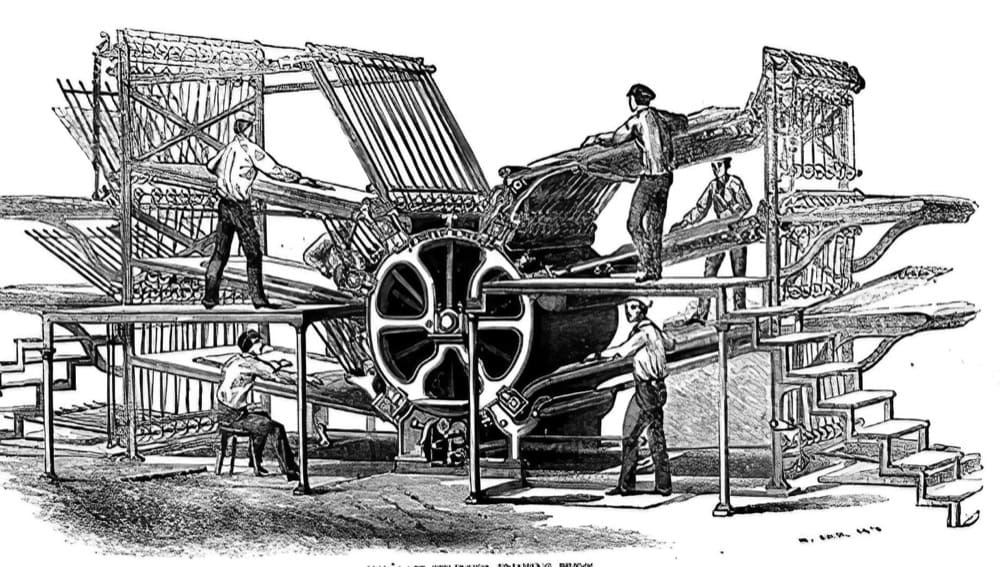

The Bullock Press: 1865

In 1865, William Bullock invented what is known today as the web press. It was the first press to be fed by continuous roll paper. The use of roll paper is important because it made it much easier for machines to be self-feeding instead of fed by hand.

Once threaded into the machine, the paper was then printed simultaneously on both sides by two cylinder forms and cut by a serrated knife. The press could print up to 12,000 pages per hour, and later models could produce 30,000 pages per hour. The first roll papers were over five miles in length.

The Typewriter: 1868

An American printer, Christopher Scholes of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is credited with inventing the first mass-produced typewriter, in 1868. Scholes’ concept was to mount printer’s type on long rods that swung towards a glass surface, which was covered with a layer of carbon paper and regular paper. When a telegraph-like key was pressed, the rod struck the carbon and left a carbon impression of the letter on the paper.

Unfortunately, the keys, which were originally in alphabetical order, tended to jam when two were struck in rapid succession. Scholes’ solution was to devise a keyboard with the most common letters spread out to slow down typing; his “qwerty” keyboard is still the standard today.

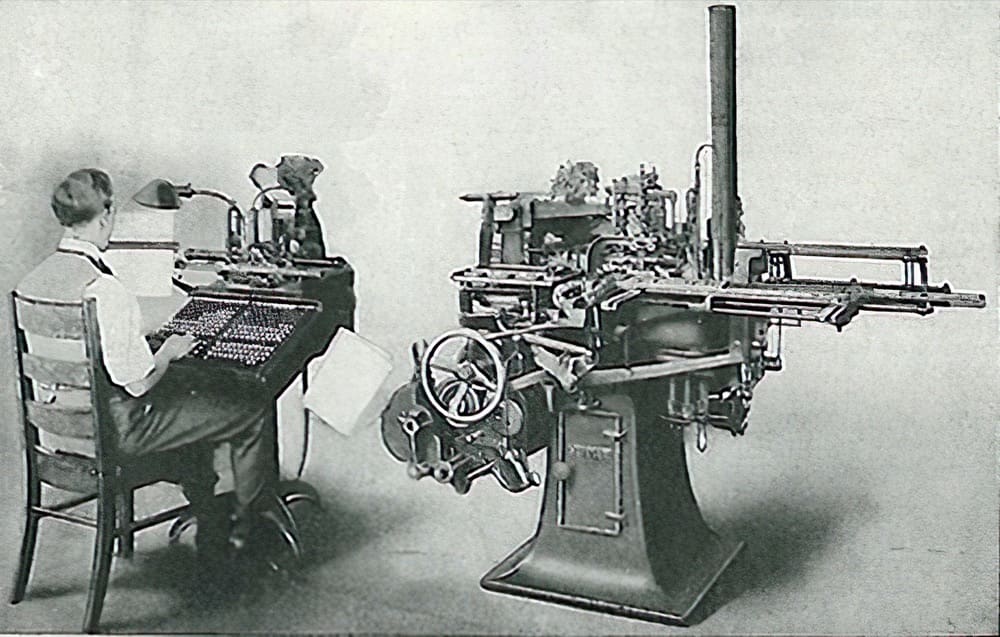

Linotype & Monotype: 1886-1889

When it was introduced in 1884, linotype represented the first major change in the mechanics of typesetting in over four hundred years. Whereas printers once had to cast type by hand, linotype allowed them to create mechanically customized type, one “line of type” at a time.

Ottmar Mergenthaler, the inventor of linotype, altered the printing process by building a machine that would custom-make letters to fit the needed document. The typesetter uses a typewriter-like device which has ninety keys to lift copper casts of letters and punctuation (called matrices) into place. Once the line is finished, a quick-cooling molten alloy is poured over the casts; when it cools, it forms a complete line of type, or “slug,” which can be set into place.

Linotype drastically shortened the time needed to create a page of type for the printing press, allowing typesetters to set more than five thousand pieces of type per hour, as opposed to fifteen hundred per hour by hand.

The invention was immediately and universally popular. In 1886, The New York Tribune became the first publication to use linotype; by Mergenthaler’s death in 1899, more than three thousand of the machines were in use, produced at three factories around the world.

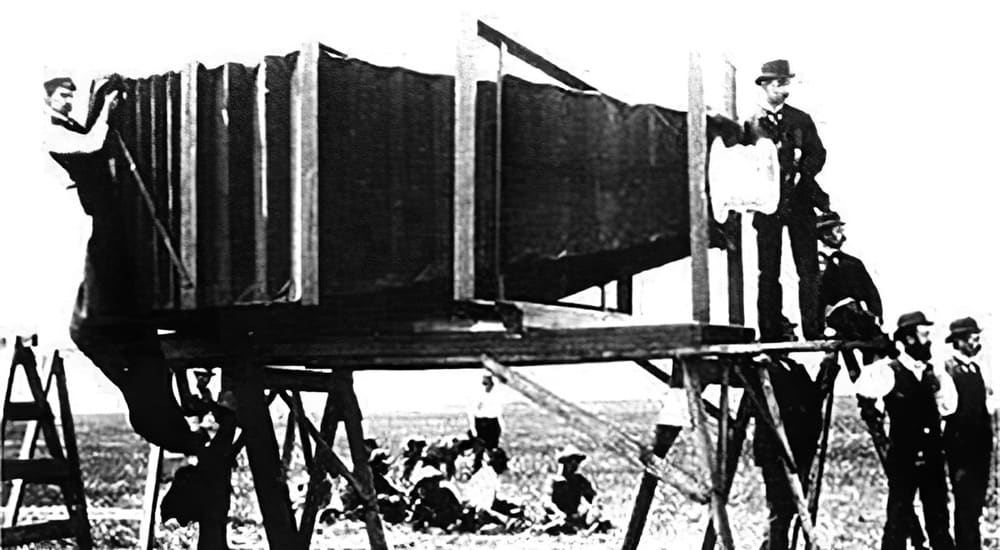

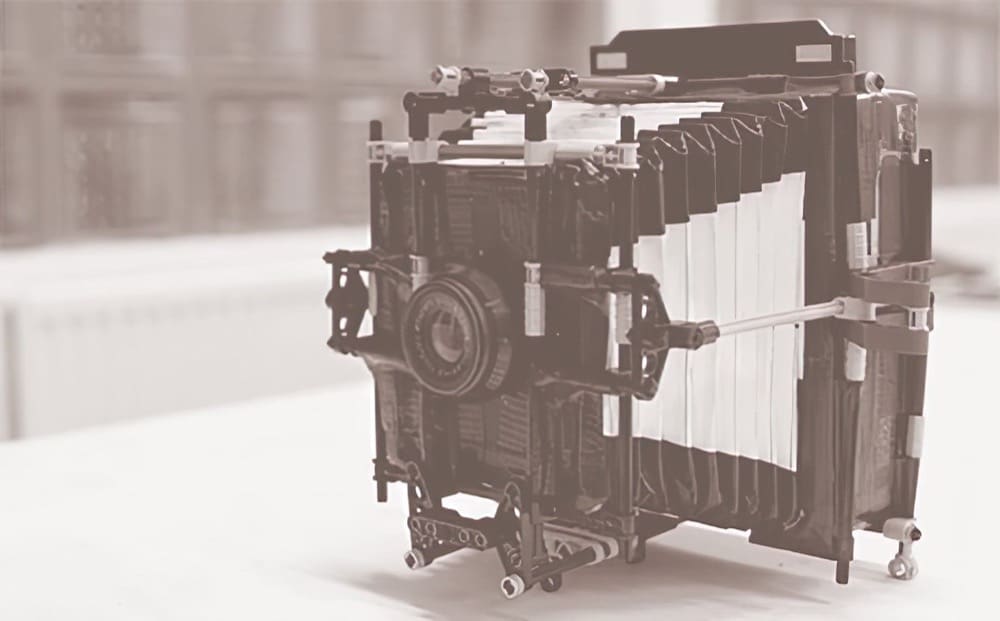

Photography: 1888

In 1888, a photographer named George Eastman invented dry, transparent, and flexible, photographic film and the Kodak cameras that could use the new film. “You press the button, we do the rest” promised Eastman with this advertising slogan for his Kodak camera.

Eastman wanted to simplify photography and make it available to everyone, not just trained photographers. In 1883, he announced the invention of photographic film in rolls. Kodak the company was born in 1888 when the first Kodak camera entered the market.

Pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures, the Kodak camera could easily be carried and handheld during its operation. After all the shots where taken, the whole camera was returned to the Kodak company, where the film was developed, prints were made, new photographic film was inserted, and then the camera and prints were returned to the customer.

George Eastman was one of the first American industrialists to employ a full-time research scientist. Together with his associate, Eastman perfected the first commercial transparent roll film which made possible Thomas Edison’s motion picture camera in 1891.

Offset Printing: 1906

The first offset press was developed by accident in 1906 by Ira A. Rubel (a paper manufacturer) by accident. An impression was un-intentionally printed from a press cylinder directly onto the rubber blanket of the impression cylinder.

Immediately afterward, when a sheet of paper was run through the press, a sharp image was printed on it from the impression which had been offset on the rubber blanket. A. F. Harris had noticed a similar effect. He then developed an offset press for the Harris Automatic Press Company in the same year, 1906.

Autochrome: 1906

Autochrome was a photographic transparency film patented in America, June 5,1906 by Auguste and Louis Lumiére. Like other techniques of the time, it employed the additive method, recording a scene as separate black and white images representing red, green and blue, and then reconstituting color with the help of filters.

To do this on a single plate, the Lumiéres dusted it with millions of microscopic (avg. size 10 to 15 microns) transparent grains of potato starch that they had dyed red (orange), green and blue (violet). Next he coated the composite with liquid shellac to totally encapsulate the grain layer.

The plate was exposed in a glass plate type view camera by placing it in the holder with the coated side away from the lens, so that when exposed, the light traversed the glass, through the grain and exposed the light/color sensitive emulsion from the back. After exposure, the plate was processed to reversal in an acid dichromate type process.

The final photograph has a beautiful look with wide tonal gradation and if you could see an original well preserved Autochrome today, you would be amazed at the extraodinary way they age, and can in fact appear as though they were processed only yesterday.

KodaChrome: 1936

Kodak introduced Kodachrome in 1936. Despite the film’s novelty, photographers quickly proved adept at adjusting to its aesthetic challenges. Rather than portraying the world naturally, Kodachrome registers intensely saturated colors – lush reds, deep blues, mercury-like chrome and silver.

These signature qualities made it the film of choice for many photographers long after other brands debuted (and its devotees were distraught when Kodak discontinued production in 2001).

Serigraphy: 1940

Most commonly known as silk-screening, serigraphy is said to have prehistoric origins, with cavemen using stencils to reproduce artowrk. Although it was first patented in the UK (1907) and then the US (1908). The company that first used the process in the US was the San Francisco Flag Company, who used silk-screen to make advertising posters. The term serigraphy was coined by a NYC artist named Anthony Velonis.

You can read more about the actual screen printing process here

Laser Printing: 1971

The first laser printer was produced by Xerox when Xerox researcher Gary Starkweather modified a Xerox copier in 1971, adding a laser beam to it to come up with the laser printer.

According to Xerox, “The Xerox 9700 Electronic Printing System, the first xerographic laser printer product, was released in 1977. The 9700, a direct descendent from the original PARC “EARS” printer which pioneered in laser scanning optics, character generation electronics, and page-formatting software, was the first product on the market to be enabled by PARC research.”

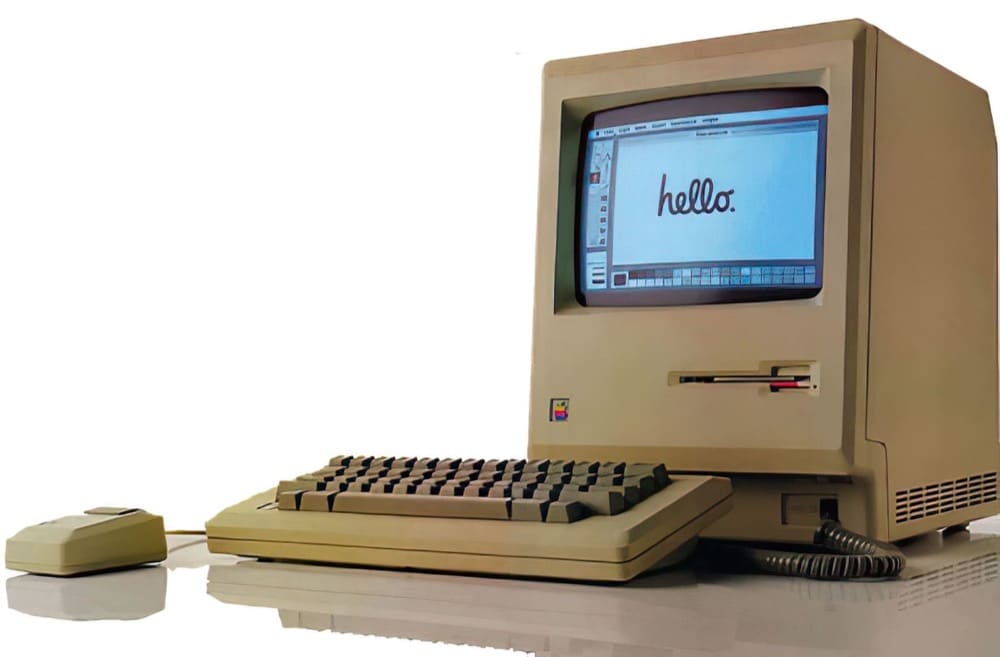

Personal Computing: 1984

Apple introduced the Macintosh to the nation in a famous ad during the third quarter of the Super Bowl on January 22, 1984.

The original Macintosh had 128 kilobytes of RAM, although this first model was simply called “Macintosh” until the 512K model came out in September 1984. It wasn’t until the Macintosh that the general population really became aware of the mouse-driven graphical user interface.

With the dawn of personal computing came a means to manipulate text and images for print applications. In the same year Apple launched Macintosh, Postscript technology was released, allowing computers to communicate with digital printers.

Desktop Publishing: 1986 - Present

Apple introduces the LaserWriter laser printer which includes Adobe’s PostScript language inside. At the same time, Aldus introduces PageMaker (the first page layout application). Desktop Publishing is born.

In 1989 Adobe shipped PhotoShop on the Macintosh which sets the standard for desktop image processing. They would go on to ship Illustrator and Indesign which also became staples of DTP. This time frame was also marked by the proliferation of digital typefaces, effectively putting an end to the days of laying out type by hand.

The convenience and speed of all these digital tools proved to be nothing short of a revolution for the world of printing.

Printing 3D: 2000 and Beyond

Z Corporation announces the release of the Z402C 3D Color Printer, the world’s first commercially available rapid prototyping device that can create physical parts in multiple colors. This revolutionary device produces parts in full 24-bit color from a range of data sources, including many native CAD formats.

This 3D printer is met with great success from many industries that were already using 3D software to build prototypes of their products and sought to eliminate the cost and time of assembly by hand.

Conclusion

Spanning centuries, the evolution of printing as artform and medium has transformed our society in countless ways - influencing the flow of ideas, information and shaping our very culture, one print at a time.